Category: Uncategorized

Haha

I’m watching this Kristin Wiig bloopers reel on YouTube. Here’s what I’m thinking, ok? Are you listening? Yeah, I knew you were. There’s this cut. This strange cut. Like an edit? You know what I mean by cut, right? I mean, look. Are you there? The “Californians” on SNL. Do you remember that? Do you remember? No, no, it’s not that clip. That one’s funny. I’m sorry. No, go ahead. Okay. Sure. Mhm. Haha. No, go ahead. Do what you need to do. Ok. Check it. It’s all good. But, see, that one from SNL is live. And that’s kind of my point. The one I’m talking about. That’s my point exactly. Are you still listening? What’s on your phone? Tell me what you’re looking at. You’re listening, ok. No, I didn’t mean you weren’t. I was just wondering. Okay, so this Kristin Wiig clip. You see, it’s like a blooper reel. But this one clip from the blooper reel is from a movie. A real movie. Haha lol. I don’t know any Kristin Wiig movies either. Good one. Not really working out for her. Maybe it was staged? Let’s circle back to that in a sec. No, I agree, she’s super talented. Hold up. Yes. Like Beyoncé. They don’t love you like I love you. Exactly. Good one. Haha. Wait, what’s up? What’s going on? Are you good? Okay, so look: this is supposed to be a blooper reel, right? Only the blooper from the movie cuts back and forth. Like shot and then reverse-shot, you know what I mean? How could it be? No, I mean this: if this shit were so spontaneous and “blooper”-like, then how is it edited? Show me a master shot or something. Otherwise the whole thing feels staged. Someone edited this blooper scene together. Lol. Yeah, I love that song. Good point. Do you want to fuck?

Okay, so I was watching this show called Mother on Netflix. Do you know that show? Okay, good. I’ve only seen like half an episode, and probably you won’t even know which one I mean, but whatever. It doesn’t matter. No, it’s all good. See you in 5. Hey, I liked your post. No, I mean I “liked” it. Yes, exactly, Mother. Alison Janney and that girl that used to be married to that guy who got in shape and then dumped her. Chris Evans. Yes, that guy. Okay, so look. No, it’s all good. Yeah. Haha. Guardians of the “Galaxy,” I get it. Good one. I dunno. Maybe Hulu. Whatever. Look. I want to tell you about this moment from this one bit of Mother I watched. Just give me a sec. Hold up. Right, exactly. They don’t love you like I love you. No, I get it. Exactly. So I’m watching this show and I’m like all bummed and weirded out because there’s a laugh track. Like Friends or something. What? Fuck that. I hate that shit. The Office, Parks & Rec: whack as FUCK. Whatever. Agree to disagree. No, exactly, the laugh track is rare these days. There’s like a legit laugh track. But check it. Amy Smart or whatever is like talking to someone in bed at night, but we can only see her. The lights are off. It’s that sitcom dark blue and white. You feel me? And then she says some shit like “if only,” or “that’s the truth,” but then she looks. Hey. What’s up? Is all good? Oh, he did? I’m legit sorry. Do you wanna talk? No, I get it. I’ll finish, but it’s not really important anymore. Considering. Lol. Ok, I’ll finish. So Kiersten Bell or Amy Smart is like, “whatever,” and you don’t hear anything. But then she looks over in the bed and the camera cuts and this guy is sleeping, like he’s been asleep this whole time, like he hasn’t been listening to her. And that’s the joke. She said something serious or something and he’s been asleep the whole time. The camera cuts and shows him asleep. And that’s when the audience laughs. You get it? The cut like contradicts what she’s been saying, and the audience laughs. The “audience.” Because if they were legit live, then they would have seen that shit earlier on the stage, seen him sleeping, before the cut, but they only laugh when the show cuts. You get it? Which means, if they’re real, if they’re actually people laughing, then they all must be watching some really whack TV show together on a screen or something, laughing at the cut, laughing way too hard about shit, and then the producers would have to take their sounds and splice them into the Netflix version. No, you’re right, it’s not that whack. I agree, she’s pretty talented. What, really? Fuck that shit. Hang in there. No, I get it. I should sleep too. Okay. Peace out. Hey, one more thing? Yeah, no, I thought the same. Haha. No, but really. Do you wanna fuck?

Fixing PDF-to-Microsoft Word Paragraph Formatting Issues in 4 Easy Steps

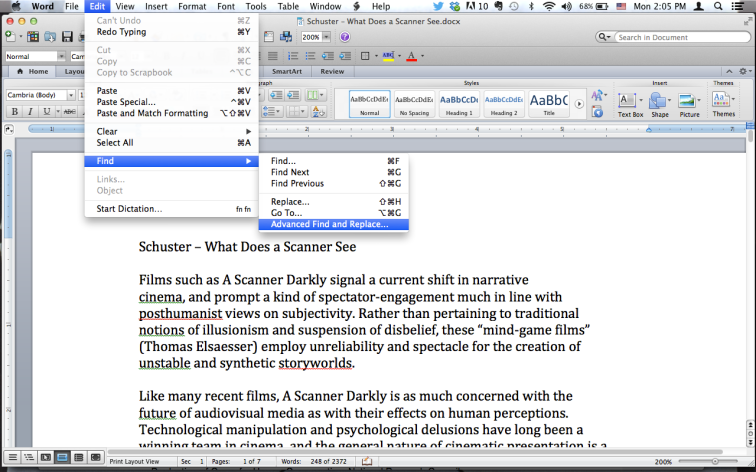

I regularly copy and paste text from PDF files into Microsoft Word 2011 for Mac, and I almost always have issues with paragraph formatting as the text moves from one interface to the other. If you look in the first image below, you’ll see that the first chunk of text is formatted strangely—the word “cinema” in the second line should not be on the second line, but the first. Essentially, Word creates paragraph breaks for every line (hence those terrible green squigglies).

One obvious, time-consuming solution is to go to the beginning of each line, press delete, space, etc. until the document is formatted the way it should be. This takes forever with long docs. But wait—there’s a better way!

Let me just say one more word about how I copy and paste text from a PDF into a Word document. If I have several passages in a PDF highlighted I’ll copy and paste them one by one. After I paste a passage into Word I hit the return key twice to create space between one pasted passage and the next. If you look at the first image below, you should be able to see how I pushed the return key twice after the word “storyworlds.” This method for fixing these PDF-to-Word formatting problems will not work exactly right unless you create that extra space between pasted passages.

Step 1: After you have copied and pasted the text from a PDF into Word, go to “Edit” then “Find” then “Advanced Find and Replace.” (If you’re using a PC or a different version of Word I’m sure the menus are similar if not exactly the same.)

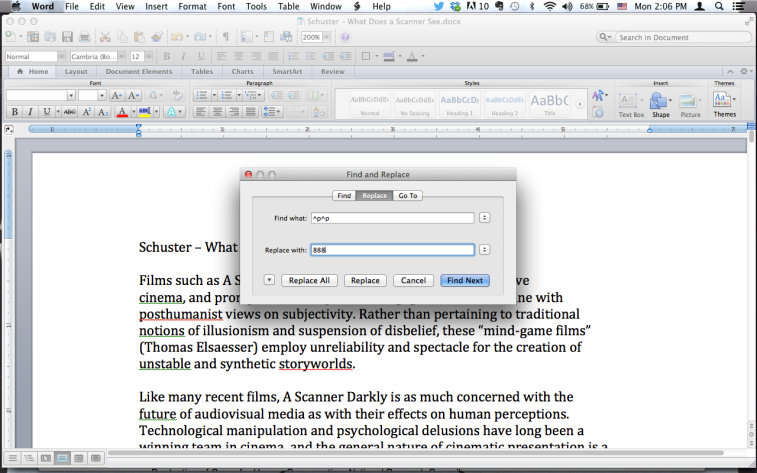

Step 2: Click the “Replace” button. In the “Find What” field, write ^p^p. (No period, though.) The carrot symbol is above the 6 on your keyboard. In the “Replace” field, write any string of letters or numbers that don’t appear in your document anywhere. I always just write “888.” I don’t know why. Click “Replace All.”

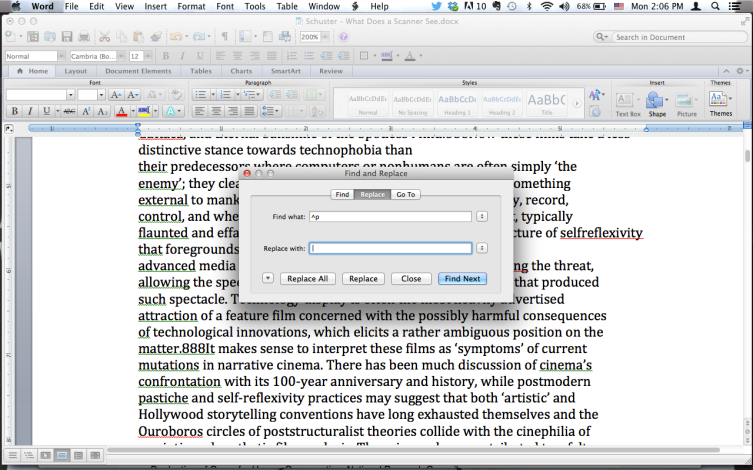

Step 3: Word will run its little calculations and do its finding and replacing. The “Find and Replace” box should still be visible (if not, just go back up to “Edit”). Now, in the “Find What” field, write ^p. In the “Replace with” field, just make a single space with the space bar. Notice the cursor in the picture below—there’s a space before it. Select “Replace All” and let Word do its business.

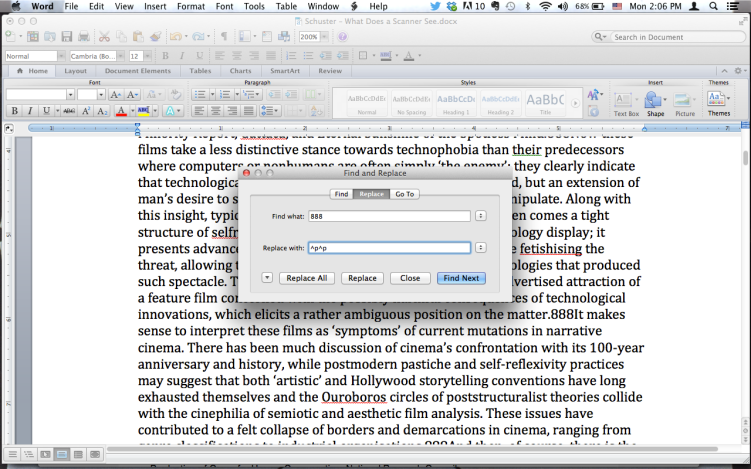

Step 4: For the final Find and Replace, in the “Find What” field write 888 (or whatever sequence you chose). In the “Replace with” field, write ^p^p and then hit “Replace All.”

That should do it. Enjoy your well-formatted document! Yeah!

FREE HAIRCUT!!!

FREE HAIRCUT!!!

If you are between the ages of 24-27 and A) own or have ever owned an XBOX system and B) have an active, regularly updated Facebook profile, then you are eligible to apply for a FREE HAIRCUT! styles vary*

*The style of cut is dependent on the contestant’s correct or incorrect answer. Haircut will be taped in front of a live studio audience on a Saturday evening in September or October (TBA).

THE LIBRARY OF BABEL

pp. 1-2

In conclusion, then, it seems clear that the gendering of mass culture as feminine and inferior has its primary historical place in the late 19th century, even though the underlying dichotomy did not lose its power until quite recently. The implications of this provide a fairly simple creative starting point for much metafictional play. The fact is (or, it follows) that writing can no longer designate an operation of recording, notation, representation, ‘depiction’ (as the Classics would say); rather, it designates exactly what linguists, referring to Oxford philosophy, call a performative, a rare verbal form (exclusively given in the first person and in the present tense) in which the enunciation has no other content (contains no other proposition) than the act by which it is uttered—something like the I declare of kings or the I sing of very ancient poets. Characters in fiction are, of course, literally signs on a page before they are anything else. This is a conceit through which a speaker effectively removes his presence from the novel and turns it over to his fictional construction, not unlike how the little boy learns that his crying is not masculine, and so he must grow into his masculinity by imitating the behavior designated as “male” to the point that such behavior becomes “second nature.” The concept of the novel, then, feeds into the (post)modern paranoia about the possibility of conspiracies or social phenomena that are carefully hidden from public discourse. In a more general perspective, however, this view implies a concept of literary evolution as improvement that I find hard to accept. The forms of art change, but do they really evolve or get better in any way? Indeed, just as a self-reflexive text must refer by default to its conservative ancestry, so the most conservative text must also contain the capacity for self-reflexivity and ironic critique: the capacity is only recognized through the act of reading.

The result is the creation of a reality sufficiently autonomous and intransitive to be explored at length as to its properties and the human condition it implies. The forces at work in these systems operate on multiple levels: underlying changes in technology that enable new kinds of entertainment; new forms of online communications that cultivate audience commentary about works of pop culture; changes in the economics of the culture industry that encourage repeat viewing; and deep-seated appetites in the human brain that seek out reward and intellectual challenge. Reality effects are designed to create the aura of real life through their sheer meaninglessness: things exist simply for background texture, to create the illusion of a world cluttered with objects that have no narrative or symbolic meaning. Even more, we should consider the burgeoning interdisciplinary field of literature and science, and the ways in which it has emerged as a notable area of inquiry. There is an effort to contribute to socialist-feminist culture and theory in a post-modernist, non-naturalist mode and in the utopian tradition of imagining a world without gender, which is perhaps a world without genesis, but maybe also a world without end. Nevertheless, the historical world is something that lies outside and beneath all our representations of it. It is a brute reality in which objects collide, actions occur, and forces take their toll.

It’s only fitting that when a playwright turns a story into a script, he has to arrange characters, events, and sentiments in a sequence of playable units or scenes. Likewise, a photograph printed using a halftone process combines discrete and continuous representations. What we must conclude, then, is that if the classic off-screen narrator is often called the Voice of God—since the audience hears his pronouncements without seeing the embodied speaker—then it is true of all desire that it depends on the infinite pursuit of its absent object. Seen in this light, the idea of private intellectual property seems almost laughable, for the image orchestrates a gaze, a limit—and its pleasurable transgression. Momentary obliviousness to being observed allows human beings to sin, according to this logic. And privacy, then, is an illusion, a dangerous illusion that promotes sinfulness. Regardless, the center also closes off the freeplay it opens up and makes possible. This fact has profound consequences for what we too hastily think of as “our” concepts, “our” readings, “our” histories, which are in an important sense not ours at all.

There are movies that are criticized because their visual effects are too striking for the narrative line to support. If this is the case, then certain films become that much more significant because they are texts that openly disrupt conventional notions of safety and the structural, narrative conventions that might provide safety, and yet crowds flock to them. That is “mass production,” not in the sense of a massive production or for use by the masses, but the production of the masses. Remember: literary forms certainly have histories and historical contingencies, and it may well be that the novel’s time as a major art form is up, as the “times” of classical tragedy, grand opera, or the sonnet sequence came to be. Along these lines, there is simply no overstating the importance of science fiction to the present cultural moment, a moment that sees itself as science fiction. After all, the imagination is poor and will be more and more easily encoded. Increasingly, men will ask machines to make them forget machines; perhaps the apotheosis of the civilized individual will be to live in an entirely novelized way. System replaces essence, which can be bad if the latter is what one searches for. But in fact, true experiments (as in science) never reach, or at least should never reach, the printed page. Fiction is called experimental out of despair. The logical evolution of a science is to distance itself increasingly from its object, until it dispenses with it entirely: its autonomy is only rendered even more fantastic—it attains its pure form. In any case, experimentation is thus not a means to an end, it is a contemporary challenge and torture.

A HAUNTING

Something very strange happened to me last night. I thought of dismissing it, of letting it waste. The incident begs to be dismissed, to be wasted. It’s an embarrassment, an interpretive fart of the first order, only possible in the 21st century.

For this to make sense, I have to provide some background, the psycho-techno setting in which I typically watch movies. We have a Mac Mini hooked up via HDMI to our HDTV. This Mac acts as our media center. This is what we see when we select HDMI 3 on the TV:

Picture 1: Mac Mini media center

If a movie isn’t available to watch instantly on Netflix, then, using Safari, I download the movie’s torrent file from bitsnoop.com and then the movie itself using uTorrent. I also hoard movies, holding on to them for a rainy day. I have Boxee installed on the Mac [second icon from the left, picture 1]; this software provides an obscenely pleasant user interface for browsing and viewing media files, those stored on the computer’s hard-drive, or on external drives:

Picture 2: Boxee’s “My Movies” interface. Essay on digital hoarding forthcoming.

I’m a graduate student. I stay up late. I try to read and write until midnight. After an hour or so of Gmail, Google Reader, etc.—everything else permitting—it’s show time. Last night I decided to watch the movie Clean, Shaven (Kerrigan, 1993). I knew very little going in, couldn’t even remember why I originally downloaded it. Boxee’s inviting description along with the Criterion pedigree and year of release were enough to convince me to give it a go. Plus, it was already 1:30 and the film is only 79 minutes.

Picture 3: Boxee’s description for Clean, Shaven. Disregard the time—that’s just the time of the screen capture.

I begin watching, bummed to discover that the movie looks like this:

Picture 4: An early shot from Clean, Shaven

Notice that black frame. I can’t stand that black frame. My TV offers three different ways of stretching the picture. I choose the option that gets rid of the frame while preserving most of the image. There’s a problem stretching the image, though. Notice the differences between pictures 5 and 6.

Picture 5: Pre-stretch, clear view of Boxee’s navigation menu / timeline, which always appears upon pause.

Picture 6: Post-stretch, notice how little of the navigation bar is now visible upon pause. (This picture is not a screen-capture, but an iPhoto rendering. The Mac’s screen-capture function doesn’t recognize changes made to the TV—it captures what it sees, not what I see.)

I had been in a rut a few months back, a time when I was unwilling to watch anything on the TV that wasn’t HD-quality, that didn’t fill up the right and left edges automatically. But there’s just too much that’s worth watching that’s only available in less-than-ideal formats. I’m willing to compromise if the movie seems worth it.

Clean, Shaven is a strange, difficult film. Every choice the director, Lodge Kerrigan, makes is in the service of occupying the mental state of a severe schizophrenic, the film’s central character, played by Peter Green. There is almost no dialogue in this film. Sounds never match images. Instead, broken, static-y noises play continually, as if we’re stuck in between channels on a radio dial, or listening to a scratched cd that isn’t quite stuck in place. We follow this character as he exits a mental hospital, tapes newspapers to his car’s windows, covers every mirror he sees with tape, stops driving to stare every time he sees a young child—altogether creepy stuff made even creepier by the soundtrack, which carries the sounds of crumpling plastic, white noise, and broken voices, all from God knows where. 20 minutes in and there hasn’t been one scene in which characters converse; 20 minutes without sounds that match images, the images themselves moving in sort-of-slow-motion, like 85% standard speed, most of the shots close-ups of trash; 20 minutes in and no narrative bearings whatsoever.

Doubt creeps in. How in the world did this movie get made? Is Kerrigan really going to keep this up? If so, is this the gutsiest movie I’ve ever seen?

My laptop and I take it outside for a five minute smoke break. I need some metatextual support, something to convince me that others have found this movie as odd and fearless as I’m finding it. This is from Dennis Lim, on the Criterion Collection website:

Lodge Kerrigan’s movies are so often termed “uncompromising” and “unrelenting” that it’s worth pondering what exactly lies behind their steadfast refusal to let up. The salient quality of these spare, intense films is that they deny the viewer the comfort of distance. Kerrigan demolishes the notion that movies are not suited to expressing inner life. He forces you to share skull space with characters most films would never think to look at, let alone so intimately. Getting close, often upsettingly so, to his lost souls and margin dwellers, he is undaunted by their opacity and failing grip on sanity, not to mention unencumbered by social judgments of any sort. In the course of three features, all as steel nerved in execution as they are rigorous in conception, this singular American independent has developed what might be the most literal and harrowing form of empathy in modern movies.

Quite a blurb. I can continue, now that I know what I’m watching is real, that it’s supposed to be like this.

And so I watch. 40 minutes pass and the film splits its narrative attention, following not only Peter, but also, separately, the detective who thinks Peter is responsible for the brutal murder of a little girl—long scenes of the detective tracking Peter, of the detective in Peter’s hotel room after Peter has left, of the detective back in his own hotel room studying the evidence, pouring over old documents, etc.

Surprisingly, disturbingly, the aesthetics of schizophrenia don’t let up during these scenes. Everything is still in a trippy not-quite-slow-motion. Nothing onscreen makes a sound. We hear only white noise and fragments of speech, some of it possibly pertaining to the detective’s search, some of it not. I begin taking notes.

Maybe these scenes of the detective are Peter’s hallucinations, his fantasies of a cop on the chase, fantasies Peter imagines in the same broken way he experiences the world. But there are no harps or fuzzy transitions, no cues that we’re cutting to a fantasy. This is potentially a radical new form of first person cinema, a movie from the point of view of someone who’s mostly somewhere else.

Maybe our access to these scenes implies another narrative presence, an overarching narrator who is also mentally disturbed, or who is somehow infected by Peter’s schizophrenia. Peter’s mental disorder certainly feels contagious from my end. Peter would have every right to be paranoid in this narrative setting, one in which the world itself is schizophrenic, in which this world watches him, if only intermittently.

Am I over-reading?

A clear aim of the film is to aggressively manifest a subjective point of view, and so to maintain the aesthetics of that subjectivity even while the film’s plot shifts into the third person is a strange move indeed, but one that the film’s attention to narration invites me to identify.

This is a narrational experiment I’m not sure I’ve seen in a film before, a strategy that suits this material incredibly well. I identify with Peter because I feel paranoid in this narrative context; everything I see is filtered through a near-omniscient, schizophrenic narration.

I write these sentences as I watch the film, a practice I’m not crazy about, but one in which the customary distractions are eased quite a bit by the film’s slowing motion—the movie is in actual slow-motion now and has been for some time. The disembodied voices aren’t quite as broken as they were before, though the image and sound still don’t connect. I can now make out little coherent bits of speech—“you stay inside all day. It’s not healthy”; “I’ll pay you back. I’ll send the money”; “he was quiet and kind as a child.” The images now correspond to the sounds from several minutes ago; the image is lagging. Sound bridges, some of them leading places, others not. As if the narrator has fragmented again, not just across space, now across time.

Picture 7

It’s 4:30.

How is it 4:30? I started watching this 79-minute movie three hours ago. I’ve only paused to take a fiver outside and one or two quick bathroom breaks.

Something is wrong with this movie.

I change the settings on the TV, reframing the image in order to see the Boxee timeline. Nothing but zeros. Boxee says that I’m at point 00:00:00 in a file that is 00:00:00 long. I tap the fast forward button on the keyboard, a button that is supposed to jump the file ahead by about ten minutes. It takes me to the very end of the movie, past the credits. Notice the timeline, colons separating hours from minutes from seconds:

Picture 8: A timeline, a broken circle.

Obviously, the file is broken. The glitch in the file slows the movie down, and then continues to slow it down for 43 hours. The movie on this file is 43 hours long.

I exit Boxee, and test the file with the trusty VLC media player. Here’s what I see:

Picture 9: VLC’s warning pop-up: “This AVI file is broken. Seeking will not work correctly. Do you want to try to fix it? This might take a long time.”

How could I let this happen? Everything I wrote about the film, everything I thought—just a broken file playing tricks on me. I’m a religious fanatic, finding God everywhere. This is an embarrassment, an indictment of everything that the general population thinks is wrong with literary and film studies. You just take that shit too seriously. You’re reading way too much into it. Your interpretation is a secondary creative work in the guise of philosophy or science. Your head is in the clouds.

Isn’t there something to be gained from this experience? What’s the meaning here?

What insanely stupid questions. The experience is a joke, a humiliation. Making anything more of it is a perpetuation of the problem. Write about it and you dig yourself deeper.

Just a broken file that Boxee is willing to play and VLC isn’t.

Why is this file broken?

The original ripper/seeder must have miscalculated something, or else was infected with a virus. Or maybe he’s brilliant, an artist; maybe this was an intentional act of torrent-textual terrorism, like sneaking a porno scene into a Toy Story file or rewriting the title cards for Birth of a Nation, only way more sophisticated, profound. Maybe it’s only my file that’s broken, or maybe it’s something on my computer that is interacting with the file, something it would take a while to sort out, something very particular to my machine, to my behavior. Maybe this is just a noticeable corruption, a corruption far more common than I thought. Every rip is an appropriation, a rewriting, in which case we have to ask what the difference is between corrupted and co-opted when it’s our condition either way.

What I watched was a very strange movie made way stranger by a technological glitch, a movie co-authored by the glitch, allowed through the gates by bitsnoop.com and by Boxee, an accidental cinema, magnificently schizophrenic.

CINEPHILIA

When your kid enjoys a Happy Meal because it comes with a car from Cars he or she is actually eating the movie. When I watch a movie on my iPad using Netflix I like to touch the actors’ faces. No two presentations of a movie are exactly the same—the aura of the original is everywhere. When I used to watch Must-See-TV on Thursday nights on NBC—Seinfeld, Cheers, LA Law, ER, Frasier, Friends, etc.—I could feel the weekend in the advertisements, the commercials for movies that will be Everywhere Tomorrow, the blockbuster promises of a Friday. I watch Weekend at Bernie’s every May to prepare for the wonders of summer. I watch Rudy or Scent of a Woman or St. Elmo’s Fire in September to prepare myself for hitting the books. I watch The Sweet Hereafter or Fargo or Nobody’s Fool in the dead of winter when it’s too cold to go outside. Every time I walk the aisles of a video store I’m overcome with a not-unpleasant desire to take a shit; I’m pretty sure this is Pavlovian: as a child I used to always read Variety and Entertainment Weekly in the bathroom. Back to the Future II is the most important American film made in my lifetime. I spend far more time refining my Netflix and uTorrent queues than I spend watching movies. From memory I can tell you where and with whom I’ve seen every movie I’ve ever seen. I’m not exaggerating. The first movie I saw in the theaters was The Neverending Story. I was three, with my mom, and we sat near the middle-back of the theater on the left side of the aisle, near the theater’s left wall. Towards the end of the movie the Empress tells Bastian that there are people enjoying his story just as he has enjoyed Atreyu’s—“people” meaning me and my mom. I’m beginning to think that this movie moment won’t ever be topped. I download movies illegally; I’m a criminal because of movies. I’ve seen Weekend at Bernie’s so many times that I feel like I can walk around inside Bernie’s beach house, like I can see every scene of the movie from any camera angle I want, like I can actually live inside of the space, like I can stretch: this is how Marty must have felt about Back to the Future in Back to the Future II. If you tell me that you like or dislike a movie or actor or director I will remember it for the rest of my life. I’m not exaggerating. I try to watch Down by Law every Thanksgiving. Is it any surprise that my favorite movies are about people who take movies seriously? Please note that I would never write “too seriously.” Badlands and True Romance are both about a guy who thinks he’s in a movie but isn’t, even though he actually is. Badlands is the tragedy and True Romance is the comedy. Think of Ferris Bueller speaking directly to the audience, staring straight into the camera. One can think of Badlands as being about a character who speaks into the camera, but slightly off-center, like he doesn’t and won’t ever know where the camera actually is—because it isn’t there, even though it is.

I saw Back to the Future in 1985 with my mom, dad, and brother. Afterwards we went to McDonald’s, still buzzing with excitement, and I had my first fish filet. It should go without saying that this was one of the 10 best days of my life. I watched 145 movies from start-to-finish last year, not as many as I should have. In the third grade my class took a field trip on a Friday morning to see The Little Mermaid. We had the theater all to ourselves. Life was the bubbles. No novel or play or videogame or painting will ever be as important to me as Weekend at Bernie’s. Jamie Lee Curtis topless in front of a mirror in Trading Places: let’s just call it a key moment in my sexual development. I fell in love with my wife in a basement in Manhattan in an Italian Neorealism course watching Fellini’s 8½. All conversations move movieward. Less than 1/10th of a second after I see a movie poster I can tell you the genre of film it advertises. I’m betting I can correctly guess whether or not you’ve seen a certain film. I’ve had to hide my knowledge of movie titles and actors’ names around friends for fear of embarrassment. I can name 20 movies starring Julia Roberts without thinking or blinking or breathing. I’ve smoked and fucked and been stoned out of my mind in movie theaters. I’ve snuck in and been kicked out. I’ve never seen Gone with the Wind or Touch of Evil or The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly or Seven Samurai or any of the Fast and the Furious movies. In my life I’ve cried more during movie previews than I’ve cried not during movie previews. I like to spend entire evenings deciding what to watch. My love for movies is indistinguishable from my love for music. There’s no topic of discussion more important than “the greatest living director.” There’s almost nothing that scares and excites me as much as the thought that I’ve somehow managed to miss a crucial scene from a favorite movie, that I’ve had to go to the bathroom or that there’s been some sort of interruption at the same point in the film each and every time I’ve watched it. My default mode of thinking is that my life is a movie watched by aliens on a distant planet, that I occupy one of 6 billion reality-TV channels serving 60 trillion aliens, that there’s exactly nothing novel or high-concept about The Truman Show. I’m also convinced that most Americans’ default mode of thinking is more or less identical to my own; that God, Facebook, etc. are just outlets and metaphors for that desire to be narrativized and watched. Nothing can secularize a nation as quickly as movies. The Internet is mostly for reading about and downloading movies. Cinema as we know it is already just a predecessor to virtual reality, an artistic-industrial-military-personal dream that will not die until it’s fulfilled. The setting for about 20% of my dreams is a movie theater—big, crowded movie theaters where the aisles are mazes and in which the stadium seating descends as you move farther away from the screen.